Floating point

The bug: 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 != 0.3

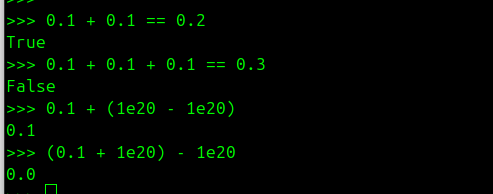

Let's test some basic calculations in Python:

- Verify that 0.1 + 0.1 equals 0.2

- That 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 = 0.3

- Or that we can change the order of calculations in an addition (that addition is commutative)

This is the real plot twist! When we test, we have 0.1 + 0.1 = 0.2 but on the other hand 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 != 0.3.

We have 0.1 + (1e20 - 1e20) = 0.1 but on the other hand (0.1 + 1e20) - 1e20 = 0.0.

A Python bug? A problem in the code? No, it’s all about how numbers are represented.

Let's explore how machines store numbers!

Base 10 vs Base 2

Let's start with the base...

We use the decimal system (base 10) daily, with 10 digits (0 to 9). In computing, we use binary (base 2), with only two digits: 0 and 1.

Each position in a binary number represents a power of 2, similar to how each position in a decimal number represents a power of 10.

For example, in our decimal system 123.45 actually corresponds to:

1 × 10² + 2 × 10¹ + 3 × 10⁰ + 4 × 10⁻¹ + 5 × 10⁻²

In binary, the number 1101.101 corresponds to:

1 × 2³ + 1 × 2² + 0 × 2¹ + 1 x 2⁰ + 1 x 2⁻¹ + 0 * 2⁻² + 1 x 2⁻³

Integer representation in base 2

In binary, integers are represented using bits (0 and 1). For example, the decimal number 13 is written in binary as 1101:

1 × 2³ + 1 × 2² + 0 × 2¹ + 1 × 2⁰ = 8 + 4 + 0 + 1 = 13

If we look at what this gives in Python:

>>> bin(13)

'0b1101'

Dtype

In Python, floating point numbers are represented using the float type, which corresponds to a double precision floating point format (64 bits) according to the IEEE 754 standard.

However, for applications requiring more precise decimal number handling, Python also offers the decimal module which allows working with decimal numbers using a base 10 representation.

In the AI domain we often adopt other data formats to shrink memory footprints. A small loss in precision is acceptable in exchange for lower memory usage and faster computation. We therefore use various data types (or dtypes) such as:

- float32 – 32 bits

- float16 – 16 bits

- bfloat16 – 16 bits

- fp8 – 8 bits

- fp4 – 4 bits

- mxfp4 – 4 bits

- nvfp4 – 4 bits

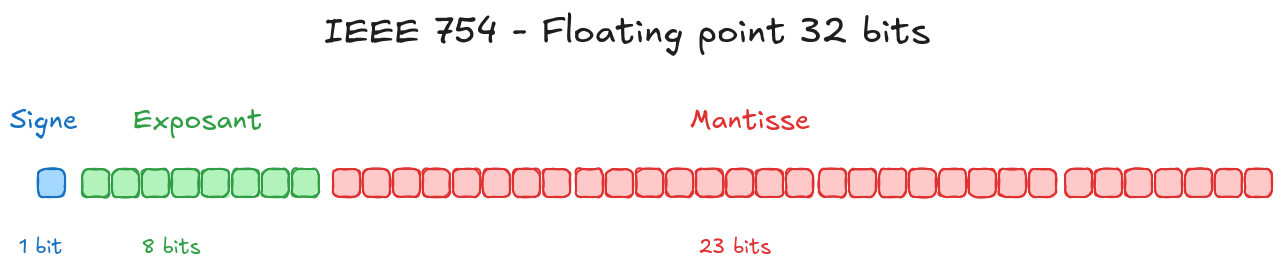

The IEEE 754 standard

The IEEE 754 standard defines how floating‑point numbers are represented in computing. A floating‑point number is made up of three main components:

Sign (1 bit): indicates whether the number is positive or negative.

Exponent (8 bits for float32, 11 bits for float64).

Mantissa or fraction (23 bits for float32, 52 bits for float64).

Because it’s a standard, the representation is the same regardless of the underlying language— a float32 will be represented identically in C, Python, or any other language that follows IEEE 754.

For example, a number in the float32 format (32 bits) is broken down as follows:

`1 bit` for the sign

`8 bits` for the exponent

`23 bits` for the mantissa (fraction)

(For reference, a float64 uses 1 bit for the sign, 11 bits for the exponent, and 52 bits for the mantissa.)

[ S ] [ Exponent (8 bits) ] [ Mantissa (23 bits) ]

0 01111111 10100000000000000000000

The actual formula is:

(-1)^sign × (1.mantissa) × 2^(exponent - bias)

Let’s break down the formula so we can understand it better.

In the following examples I’ll focus on float32, but the same reasoning applies to float64, or even to formats like fp8.

Sign

We need to be able to represent both positive and negative values, such as 3.14 or ‑0.123.

The sign bit determines whether the number is positive or negative.

If the sign bit is 0, the number is positive.

If the sign bit is 1, the number is negative.

Exponent

Our goal is to be able to represent both very large and very small numbers.

The IEEE 754 standard does this by using scientific notation.

In base 10scientific notation a number is written as

value = mantissa × 10^exponent

with the mantissa in the form 1.xxx

Examples:

3.14 = 3.14 × 10^0

0.00314 = 3.14 × 10^-3

3140 = 3.14 × 10^3

In base 2 we use the same idea, but with powers of 2:

value = mantissa × 2^exponent

with the mantissa in the form 1.xxx

Because we want to cover numbers that are both huge and tiny, the exponent can be negative as well as positive.

For a float32 the exponent is stored in 8 bits.

Binary patterns therefore range from 00000000 to 11111111 a total of 2⁸ = 256 possible values.

These values encode exponents that run from ‑127 to +128 (note that the edge values ‑127 and +128 are reserved cases that are described later).

The question is: how do we map the bit patterns [00000000, 11111111] to the exponent range [‑127, +128]?

We use a bias of 127.

That means the real exponent is obtained by subtracting 127 from the stored value.

Example

If the stored exponent is 10000011→ 2⁷ + 2 + 1 = 131

→ true exponent = 131 – 127 = 4

The general rule for computing the bias is

bias = 2^(number_of_exponent_bits – 1) – 1

For float32 (8 exponent bits) this gives

bias = 2^(8–1) – 1 = 127

Mantissa

The mantissa (or fraction) holds the significant part of the number.

In a float32 it is stored in 23 bits.

Those 23 bits actually represent 24 bits of information —the reason being that the mantissa is always of the form 1.xxx.

The leading 1 is implied; we don’t need to store it.

Consequently, only the bits that come after the binary point are kept in the mantissa field.

Example

If the stored mantissa bits are 10010010000111111011011 the real value is actually 1.10010010000111111011011

Because the hidden leading 1 is automatically present for all normal (non‑subnormal) floating‑point numbers.

Notation

When we describe an IEEE 754‑style format, it’s common to use a shorthand that specifies only the exponent‑width and the mantissa‑width.

For example, an 8‑bit floating‑point format (fp8) might be written as:

Shorthand Meaning

E4M3 4‑bit exponent, 3‑bit mantissa

E5M2 5‑bit exponent, 2‑bit mantissa

The “E” stands for the exponent field, the number that follows is the width (in bits), and “M” stands for the mantissa (fraction) field. This notation makes it easy to talk about custom or reduced‑precision formats without having to write out the full binary layout.

Special cases

Zero

A keen reader will wonder: how can we represent the number 0with this format?

That’s impossible if we start from a mantissa of the form 1.x and multiply it by ±1 (according to the sign) and by 2^exponent.

To encode zero we use a special convention: when both the exponent and the mantissa are zero, the value is interpreted as zero (positive or negative depending on the sign bit).

Consequently, the format defines two separate zero representations: +0 and ‑0.

Infinity

Similarly, a special convention represents infinity.

When the exponent is all‑ones (the maximum value) and the mantissa is zero, the value is interpreted as infinity (positive or negative according to the sign bit).

NaN

NaN means “Not a Number” – a special value used when a calculation has no meaningful numerical result.

Examples: 0/0, ∞ − ∞, etc.

By convention, we obtain a NaN when the exponent is all‑ones (maximum) and the mantissa is non‑zero.

Conversion

To convert a decimal number to its binary floating‑point representation according to the IEEE 754 standard, follow these steps:

1. Determine the sign: `0` for positive, `1` for negative.

2. Convert the integer part and the fractional part of the number to binary.

3. Normalize the binary number to obtain the mantissa in the form `1.x`.

4. Compute the exponent, adjusting it with the bias.

5. Assemble the sign, exponent, and mantissa to produce the final representation.

Example 1

Let’s start with a simple example using the number 1.625.

- Sign:

1.625is positive, so the sign bit is 0. - Binary conversion:

Integer part 1 → 1 in binary.

Fractional part 0.625 → 0.101 because

0.625 = 1/2 + 1/8 = 1·2⁻¹ + 0·2⁻² + 1·2⁻³.

Therefore 1.625 in binary is 1.101. - Exponent: The integer part is 1·2⁰; the real exponent is 0.

We store real_exponent + bias, i.e.0 + 127, which in binary is01111111. - Mantissa: The normalized mantissa is

1.101.

Drop the leading1.we keep101and pad with zeros to 23 bits:

10100000000000000000000. - Assembly: Combine the sign, exponent, and mantissa:

Sign:0

Exponent:01111111

Mantissa:10100000000000000000000

Final binary representation:0 01111111 10100000000000000000000

Example 2

Let's take another example -12.345

1. Sign : -12.345 is negative so the sign bit equals 1

2. Binary conversion

For the integer part:

Division Quotient Remainder

12 ÷ 2 6 0

6 ÷ 2 3 0

3 ÷ 2 1 1

1 ÷ 2 0 1

Reading the remainders from bottom to top gives the binary representation of the integer part: 1100 (which is 12 in decimal).

Fractional part

0.345 × 2 = 0.690 → integer part I = 0

0.690 × 2 = 1.380 → integer part I = 1

0.380 × 2 = 0.760 → integer part I = 0

0.760 × 2 = 1.520 → integer part I = 1

0.520 × 2 = 1.040 → integer part I = 1

0.040 × 2 = 0.080 → integer part I = 0

0.080 × 2 = 0.160 → integer part I = 0

0.160 × 2 = 0.320 → integer part I = 0

0.320 × 2 = 0.640 → integer part I = 0

0.640 × 2 = 1.280 → integer part I = 1

We stop here for illustration, but you must keep multiplying by 2 until you have gathered the full 23 bits that will form the mantissa.

Reading the integer parts E in order

When we read the successive integer values that come out of the fractional‑multiplication steps, we obtain 0.0101011100...

So, -12.345 in binary is 1100.0101011100...

3. Normalisation

We shift the binary point three places to the left to obtain the normalised form 1.1000101011100... × 2^3

The real exponent is 3, so we store real_exponent + bias = 3 + 127 = 130 which is 10000010 in binary

4. Mantissa

We drop the implicit leading 1. from the normalised mantissa and keep the remaining fraction: 1000101011100...

5. Final result (with the full mantissa):

- Sign: 1

- Exponant: 10000010

- Mantissa : 10001011000010100011111 (23 bits)

- Final binary representation : 1 10000010 10001010111000010100011

Limitations

Floating‑point numbers have inherent limits on precision and range. Some decimal values cannot be represented exactly in binary, which can lead to rounding errors in calculations.

For example, the decimal number 0.1 has no exact binary representation.

If you run the algorithm described above on 0.1, you’ll encounter an endlessly repeating pattern in the mantissa - specifically the cycle 1001. Since memory is finite, a float32 will store only the first 23 bits of that cycle, while a float64 will store 52 bits. The result is more precise, but still not exact.

The same issue occurs in base‑10 when attempting to encode 1/3 = 0.333333…; you can’t capture the true value with a finite sequence of bits.

In float32, the binary encoding of 0.1 is:

`0 01111011 10011001100110011001101`

which, when converted back to decimal, corresponds to 0.10000000149011612. The tiny difference from the intended value is the rounding error introduced by the floating‑point format.

Such inaccuracies can produce unexpected results in numerical computations.

>>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 - 0.3

5.5511151231257827e-17

Ou encore

>>> 1.1 + 2.2

3.3000000000000003

Going further

Decimal vs. Binary floating‑point

Python offers the decimal.Decimal module for calculations that obey base‑10 arithmetic. This eliminates the rounding‑error problems of binary floats, but it does so at the cost of larger storage and slower execution.

from decimal import Decimal

print(0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1)

print(Decimal("0.1") + Decimal("0.1") + Decimal("0.1"))

0.30000000000000004

0.3

A typical example would be financial calculations, where you absolutely want to avoid rounding errors.

https://docs.python.org/3/library/decimal.html#module-decimal

Practical implications

Understanding floating point representation is crucial for:

- Financial calculations (use decimal module instead)

- Scientific computing (be aware of precision limits)

- Equality comparisons (never use == with floats)

Instead of:

if a == 0.3: # Don't do this!

print("Equal")

Use:

import math

if math.isclose(a, 0.3):

print("Equal")

Conclusion

Floating point numbers are an approximation of real numbers, constrained by the finite precision of computer memory. The IEEE 754 standard provides a consistent way to represent these approximations, but understanding its limitations is essential for writing robust numerical code.

The next time you see floating point "bugs", remember: it's not a bug, it's a feature of how computers represent infinite precision mathematics in finite memory!

Ressources

- Python floating point https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/floatingpoint.html

- Numpy : https://numpy.org/doc/stable/user/basics.types.html

- Utilisation de FP8 dans Deepseek https://arxiv.org/pdf/2505.09343